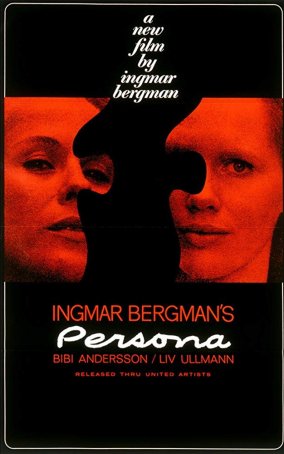

Persona (Sweden, 1966)

April 05, 2019

In the community of elite critics, there are those who would claim that Persona is the best film ever made, placing it in the rarified atmosphere of such classics as Citizen Kane, City Lights, and Tokyo Story. Although I would agree that Persona is a very good film and stands on the doorstep of director Ingmar Bergman’s most fertile period as a filmmaker and storyteller, I don’t believe it’s representative of Bergman’s best (that would be Cries and Whispers), let alone deserving of a place at cinema’s pinnacle. Persona is notable for its unforgettable photography, haunting performances, and puzzling screenplay. The storyline is so abstruse that it can mean something different to everyone; there is no definitive interpretation. Some will find that gratifying; others will find it maddening. This style of movie-making – a cross between outright experimentation and accomplished craft – found a more receptive audience at the time of its release than it would find today. Times have changed, tastes have modified, and the era of the auteur as a spinner of open-ended ambiguity is past.

(Spoilers follow…)

The plot is seemingly straightforward. A famous actress, Elisabet Vogler (Liv Ullmann), has lost her voice. A nurse, Alma (Bibi Andersson), is assigned to her case – to act as her companion and helper during a seaside vacation. While there, a closeness develops. In an unguarded moment lubricated by too much alcohol, Alma reveals details of an orgy she once participated in. Her expectation that this story will remain in strict confidence is betrayed; she discovers that Elisabet has written about it in a letter. This fractures the nascent friendship and creates a series of escalating conflicts that result in Elisabet regaining her speech but perhaps losing something more important.

Perhaps the most salient question about Persona is to what degree the film’s narrator can be considered

reliable. This uncertainty is introduced at the outset during a montage

featuring subliminal images and disconnected clips that emphasize that this

movie (like any movie) is merely a collage of sounds and images put together by

a director. Bergman returns several more times to this method of

deconstruction: once when the film appears to “break,” once when he shows an

eight-minute monologue twice (once focusing on Alma’s face as she speaks and

once on Elisabet’s features as she listens), and once at the end when he

depicts a crew filming a scene that makes the characters’ fates uncertain.

Perhaps the most salient question about Persona is to what degree the film’s narrator can be considered

reliable. This uncertainty is introduced at the outset during a montage

featuring subliminal images and disconnected clips that emphasize that this

movie (like any movie) is merely a collage of sounds and images put together by

a director. Bergman returns several more times to this method of

deconstruction: once when the film appears to “break,” once when he shows an

eight-minute monologue twice (once focusing on Alma’s face as she speaks and

once on Elisabet’s features as she listens), and once at the end when he

depicts a crew filming a scene that makes the characters’ fates uncertain.

Bergman hints, but never explicitly reveals, that Alma and Elisabet may be separate halves of one person. To that extent, perhaps there is no “Elisabet” – she may simply be a subconscious representation of something repressed deeply within Alma. Or perhaps “Alma” is just another role played by Elisabet. (The ending argues for the former interpretation. There is a quick shot of a woman – presumably Elisabet – lying supine, possibly dead. At the same time, Alma is shown leaving the seaside by herself.) At one point, Bergman creates an image that is comprised half of Bibi Andersson’s face and half of Liv Ullmann’s.

Or perhaps there’s something parasitic going on – a synergy between the two that has them feeding off one another. Vampirism is hinted at – there’s a blood-drinking scene and at least one instance when one character nuzzles the neck of the other. Less thinly-veiled are indications of lesbianism. One could make a case that the characters have sex although those who oppose this interpretation offer valid counter-claims.

Bergman’s attraction to the actresses (he had affairs with

both – Anderssen prior to filming Persona

and Ullmann afterward) is evident in the way he and cinematographer Sven

Nykvist film them. There are a great number of close-ups and the

black-and-white film allows a more emphatic use of shadow. At times, the camera

lingers on their eyes, as if focusing on them can reveal a glimpse of the soul.

Hair is usually pulled back to give a naked view of the face and, as the movie

progresses, there is a conscious effort to enhance the resemblance between Alma

and Elisabet – indications that if this is some form of split personality, it

may be merging.

Bergman’s attraction to the actresses (he had affairs with

both – Anderssen prior to filming Persona

and Ullmann afterward) is evident in the way he and cinematographer Sven

Nykvist film them. There are a great number of close-ups and the

black-and-white film allows a more emphatic use of shadow. At times, the camera

lingers on their eyes, as if focusing on them can reveal a glimpse of the soul.

Hair is usually pulled back to give a naked view of the face and, as the movie

progresses, there is a conscious effort to enhance the resemblance between Alma

and Elisabet – indications that if this is some form of split personality, it

may be merging.

Bergman maintained that he had an idea what the film meant but he wouldn’t reveal it because he wanted each viewer to have his/her own interpretation. In a 1970 interview, he stated that the core idea underlying the movie was that of the fleeting nature of consciousness and existence. There are times when this concept emerges as part of an explanation for why Elisabet can’t (or won’t) speak: she has become weary and disillusioned and wants to “turn off.”

If one prefers a more literal and concrete understanding of Persona, it can be seen as a

psychological horror/thriller with some bizarre ellipses. The music is spooky

and discordant and there’s something intrusive and at times claustrophobic

about the use of so many close-ups. There are even a couple of stingers that

could be seen as presaging the modern “jump scare” – moments when the music

jangles to emphasize a disturbing image.

If one prefers a more literal and concrete understanding of Persona, it can be seen as a

psychological horror/thriller with some bizarre ellipses. The music is spooky

and discordant and there’s something intrusive and at times claustrophobic

about the use of so many close-ups. There are even a couple of stingers that

could be seen as presaging the modern “jump scare” – moments when the music

jangles to emphasize a disturbing image.

Persona won Bergman much critical acclaim but the film was a box office disappointment both in Sweden (where it was released generally) and in the United States (where it was given a limited run). The movie wasn’t without controversy and censorship demanded edits in both the U.S. and the U.K. (The quick shot of an erect penis at the beginning was removed and parts of Alma’s confession were left untranslated in the subtitles.) The version currently available on DVD is a restored edit that includes the “missing penis” and has all of the dialogue incorporated and subtitled.

Arguably the most rewarding aspect of Persona is its rewatchability. The movie’s themes are so complex and deeply buried that it offers something new each time it is seen. Like a Rorschach test, one’s interpretation says more about the person offering the opinion than the film itself. It’s a fascinating motion picture, built with intellectuals, film students, and lovers of the inscrutable in mind. Emotionally, however, it’s cold and unlovable – an exercise designed to engage the mind while leaving the heart unmoved. Persona is critical to a wider understanding of Bergman as a person and a filmmaker and represents one of his most dissected and discussed contributions to ‘60s cinema.

Persona (Sweden, 1966)

Cast: Bibi Andersson, Liv Ullmann

Home Release Date: 2019-04-05

Screenplay: Ingmar Bergman

Cinematography: Sven Nykvist

Music: Lars Johan Werle

U.S. Distributor: United Artists

U.S. Release Date: -

MPAA Rating: "NR" (Sexual Content, Profanity, Brief Nudity)

Genre: Drama/Thriller

Subtitles: In Swedish with subtitles

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 1.33:1

- (There are no more better movies of Bibi Andersson)

- (There are no more worst movies of Bibi Andersson)

- Cries and Whispers (1972)

- (There are no more better movies of Liv Ullmann)

- (There are no more worst movies of Liv Ullmann)

Comments