Patton (United States, 1970)

"Through the travail of ages

Midst the pomp and toils of war,

Have I fought and strove and perished

Countless times upon a star.

As if through a glass, and darkly,

The age-old strife I see,

For I fought in many guises, many names,

But always me."

- Gen. George S. Patton, Jr.

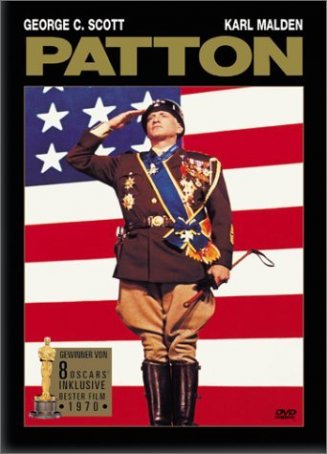

In early 1971, the Academy Awards saluted Patton. Capturing eight Oscars- including best picture, best director, best actor, best screenplay, best editing, and best production design - the movie won every major battle of the evening. Such acclaim was richly deserved, for Patton remains to this day one of Hollywood's most compelling biographical war pictures.

With its larger-than-life, yet at the same time singularly human, portrayal of Gen. George S. Patton, Jr., Franklin Schaffner's picture is an example of filmmaking at its finest. From production design and battle choreography to simple one-on-one dramatic acting, Patton has it all. There is no scene in all one-hundred seventy minutes that doesn't work on some level.

Patton was not a friendly, easygoing person. A war hero and a keen strategist, he was also harsh, stubborn to the point of intransigence, and undiplomatic. Aside from the campaigns he waged in North Africa, Sicily, and across Europe, the general is perhaps best remembered for an incident when he slapped an enlisted man. The news media of the time vilified him for this, and the history books have been little more kind. That single act, more than anything, typified the national perception of him.

That side of the man is shown in Patton, but there are more facets to the general's personality than what he presented in public. There was also the deeply thoughtful philosopher, who believed in God and destiny, and accepted reincarnation (he believed that he had been on the battlefield when the Carthaginians fought the Romans, and had later served with Napoleon). Patton was neither cold nor insensitive - he cared deeply about those under his command who stood in the face of enemy fire and refused to yield. In its evenhanded presentation, Patton does justice to those aspects of the general's character, in addition to the more obvious ones. What we see is not a legend, but a man, with all the flaws and triumphs that made him who he was.

Into the role stepped George C. Scott, giving the performance of a long and impressive career. Indeed, Scott became so identified with the character, and played the general so perfectly, that the Patton of documentaries has since occasionally been referred to as "an imposter." In a part that requires a skillful scaling of the emotional ladder, Scott finds the perfect balance between bombast and subtlety. From the opening scene (the famous speech to the Third Army in front of the giant American Flag), the viewer's attention is riveted to the screen, and only when the final credits roll do external distractions reassert themselves. It is no exaggeration to say that, in the decade of the seventies, only men like Brando, Pacino, Nicholson and De Niro equalled what Scott accomplished in Patton.

The film opens in 1943 North Africa, with a brutal look at American casualties at the battle of Kasserine. Patton arrives from Morocco to take command the U.S. army in Tunisia in preparation for fighting Rommel (Karl Michael Vogler) at el Gitar. From North Africa, Patton's forces move to Sicily, where they sweep north across the island, taking Palermo, then racing Montgomery (Michael Bates) to Messina. Along the way, Patton's verbal and physical abuse of a soldier suffering from "battle fatigue" - which the general brands as cowardice - becomes ammunition for his critics. He later offers a public apology, but this incident keeps him from the action for a while, and he must stand by as a decoy during the Normandy invasion. Later in the year, however, General Omar Bradley (Karl Malden) gives Patton command of the Allied Third Army, with which he pushes across Western Europe to stop the Germans at the Battle of the Bulge, the last major Nazi offensive of the war.

With the exception of Patton, the only character given more than cursory attention is Omar Bradley, who is shown to be a conservative, level-headed antithesis to Patton's impulsive, ill-tempered bluster. Bradley begins the film serving under Patton, and ends it as his superior. The two are friends, but each finds fault with the other's methods. As Bradley says, "I do this job because I've been trained to do it. You do it because you love it."

The statement that Patton "is [his] own worst enemy" is proven repeatedly. After the slapping incident, while the general is essentially on probation, he makes some comments that he believes to be off-the-record. The press prints them, and Patton is seen as having insulted the "Russian Allies." by claiming that the United States and England would jointly rule occupied Europe following the war. In order to get back into favor with his superiors, Patton must promise to keep his "big mouth shut."

Patton manages the intricate task of presenting personal details in the larger context of their historical backdrop. We observe detailed recreations of the battles of el Gitar, Sicily, and the Bulge, even as Patton's own desires, needs, and hopes are exposed through his actions and conversations. The most defining moments for the general as a person often come when he's alone with his aide, or facing his own mortality as he gazes across battlefields that are millennia old.

Fred Koenkamp's photography does justice to the picture's material. Not only does he have a good sense of how to capture a battle on film, but he is equally adept at framing the quieter, more personal moments. The last shot of the film, with Patton walking his dog across a snow-spotted field in Bavaria, blends the best of both these intimate and panoramic views. Jerry Goldsmith's fine - and immediately recognizable - score compliments Koenkamp's cinematography.

Those who have not seen Patton, or who have not watched the film carefully, might assume that this movie is about World War Two and one of its most celebrated generals. In fact, they would be only partially correct. What Patton sets out to do is to demythicize its subject and show the forces that drove this man.

Brilliant tactician, merciless disciplinarian, tireless fighter, prima donna, and staunch patriot - Patton was all of these things and more. Life for him was the battlefield, and without war, his spirit was sapped. The German military recognized this when they noted that Berlin's fall would finish him. Patton was an anachronism - a man who belonged in another time. He was a warrior living in a time when victory in battle no longer meant the triumph it once had, a Roman conqueror who understood the meaning of the words that "all glory is fleeting." Above all, however, he was an icon whom millions cheered, millions hated, and few understood.

Patton (United States, 1970)

Cast: George C. Scott, Karl Malden, Michael Bates, Karl Michael Vogler, Edward Binns, Paul Stevens

Screenplay: Edmund H. North and Francis Ford Coppola based on factual material from Patton: Ordeal and Triumph by Ladislas Farago and A Soldier's Story by Omar N. Bradley

Cinematography: Fred J. Koenkamp

Music: Jerry Goldsmith

U.S. Distributor: 20th Century Fox

U.S. Release Date: 1970-04-02

MPAA Rating: "PG" (Violence, Profanity)

Genre: DRAMA/WAR

Subtitles: none

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 2.20:1

- Dr. Strangelove (1969)

- Hustler, The (1961)

- (There are no more better movies of George C. Scott)

- (There are no more worst movies of George C. Scott)

- On the Waterfront (1954)

- (There are no more better movies of Karl Malden)

- (There are no more worst movies of Karl Malden)

- Clockwork Orange, A (1969)

- (There are no more better movies of Michael Bates)

- (There are no more worst movies of Michael Bates)

Comments