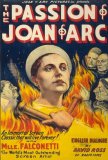

Passion of Joan of Arc, The (France, 1928)

February 02, 2010

The story of Joan of Arc (properly Jeanne d'Arc) has been a staple of the cinema since the medium was invented. In fact, due to the canonization of Joan in 1920, her tale was more popular in the early days of movies than it has been in recent times. All told, more than three-dozen versions of her tale have been filmed - many silent and all but the most notable lost to the neglect that has claimed a majority of less celebrated motion pictures. Fortune has played a significant part in the survival of Carl Th. Dreyer's unique, remarkable take on the legend of the French heroine, The Passion of Joan of Arc.

For this movie, Dreyer, a respected Danish director (remembered also for 1932's Vampyr), elected to approach Joan's mythology from a different perspective than anything that had been previously (or was subsequently) attempted: by confining the story to her trial, with no flashbacks and few references to her life preceding her appearance before the ecclesiastical court at Rouen. For Dreyer, Joan's rich and varied life offered little relevance to the themes he was exploring. Assuming those attending the film would be aware of the background, he did not waste valuable screen time reflecting upon it. (Today, that would fall into the category of "overestimating the intelligence of the audience.") Anyone approaching this movie with little or no knowledge of the title character's history would only be able to determine from the text that she was a controversial figure who believed her visions originated from God, but which the Church leaders argued were Satanic in origin. Those searching for a more complete biography of Joan's life will have to look elsewhere, and there is no shortage of alternatives (both in print and on film).

Joan's trial lasted more than 4 1/2 months, beginning in January 1431 and concluding in May. She was executed on May 30 by being burned at the stake. In order to focus the drama, Dreyer elected to condense Joan's trial into a single day, but much of the film's dialogue is derived from first-hand accounts of the proceedings. He simplifies things to prevent the story from becoming overly complicated or unmanageable. Dreyer's themes relate to the power of faith and the manner in which those who claimed the title of religious leaders destroyed the life of a pure young woman. Other elements - such as the political nature of the trial and charges of witchcraft - have been elided from The Passion of Joan of Arc because their inclusion would not have made this a better motion picture.

The narrative is straightforward. Joan (Maria Falconetti in an iconic performance) is brought into court to face charges of heresy and blasphemy. Her accuser is Bishop Pierre Cauchon (Eugene Silvain), who remains her adversary throughout the proceedings. He lays various semantic traps for her, all of which she neatly bypasses. The most dangerous of these occurs when Cauchon, believing he has maneuvered Joan into an untenable position, demands to know whether she is in a State of Grace. If she answers "yes," she will condemn herself since, as a matter of Catholic doctrine, no person can know this for sure. If she answers "no," she will admit to being a liar and a heretic. Her response is perfect for the situation: "If I am not, may God put me there! And if I am, may God so keep me!"

The contest of wills between Joan and Cauchon continues beyond the courtroom. She is taken to the torture chamber, where the appearance of the devices and machines causes her to swoon. The doctors care for her, since Cauchon does not want her dying of natural causes, and restore her to health and vitality. As her execution is being prepared, she experiences a change of heart and recants, denying the divinity of her visions. Her death sentence is commuted to one of life in prison (with only a diet of bread and water). Almost immediately, however, she changes her mind, believing her previous plea to be a betrayal of her faith. She is executed and a mob, convinced she was sent by God, riots. (This event is an invention of Dreyer's - Joan's real-life burning did not provoke public unrest.)

Some 20 years after Joan's death, the Catholic Church launched an investigation into the circumstances surrounding her trial and execution. The end result was for her to be declared innocent of the charges. The reversal classified her as a martyr and branded her accuser, Bishop Cauchon, as a heretic whose blind and biased pursuit was based on a secular, not a religious, foundation. Her rehabilitation was finalized in 1920, when the Catholic Church canonized her.

The Passion of Joan of Arc unspools more like a documentary than a traditional drama. It is predominantly a recreation of the trial and rarely deviates from that objective. Dreyer's attention to detail is exacting. For example, during the scene in which Joan is treated for a fever, the director films an actual bleeding (although the arm is that of a double, not actress Maria Falconetti). No special effects are utilized. The incision and subsequent bloodletting are real. For the second take, the blood did not flow as freely and had to be "coaxed out."

The stylistic element most often remarked upon in discussions of The Passion of Joan of Arc is Dreyer's reliance upon close-ups. Of the more than 1500 shots in the movie, around 80% of them are single-face close-ups. Establishing shots are few and there are almost no mid-range images or extended, unbroken takes. Some contemporary critics were disturbed by Dreyer's "over-reliance" on close-ups, but the director's purpose - to enhance the psychological tension of scenes by fixing the camera on the face - has withstood the test of time. The Passion of Joan of Arc is memorable in part because of the methodology. In an era when most Hollywood productions of a similar length possessed around 600-700 shots, The Passion of Joan of Arc boasted more than twice as many cuts. This sort of editing room assembly will not disconcert modern-day viewers. 21st century directors rely on shot numbers that often exceed Dreyer's, but for a silent-era motion picture, this was unconventional and perhaps unprecedented. (Not enough pre-talkies exist to make a definitive determination.)

To emphasize the primary theme of holding fast to one's faith despite seemingly insurmountable obstacles, Dreyer structures The Passion of Joan of Arc like a passion play (hence the title), with numerous allusions to the Passion of Jesus, from the frequent crucifix imagery to the straw crown. A secondary theme that dovetails with this is the unjust weight of the Religious Establishment being brought to bear on a "child of God." With Jesus, it was the Pharisees and Pontius Pilate who, unable to find just cause to condemn their victim, trumped up charges. In this case, it is Cauchon twisting ecclesiastical law to condemn Joan. As represented in the movie, this is a power play on his part. He must either discredit Joan or kill her in order to maintain his authority. (The role played by the English in Joan's condemnation is hinted at but not explicitly revealed. In reality, Cauchon has long been accepted as a puppet of the then-conquerors. Rouen was under British occupation at the time of the trial.)

The film's positive thematic content lessens the downbeat impact of the ending. The protagonist dies but, in doing so, she embraces injustice in order to validate her faith. She wins; Cauchon loses, even though it might seem superficially otherwise. Dreyer's invented riots emphasize the point, but they are not needed. Indeed, their inclusion might be the film's only misstep. The political climate of Rouen is not sufficiently developed for them to be seamlessly interwoven into the story's overall fabric.

When one speaks of The Passion of Joan of Arc, the first image to come to mind is the beatific face of Maria Falconetti, whose expressive features give voice to the movie's silence. She speaks with her eyes in ways that mere dialogue could not achieve. Dreyer's use of close-ups serve her well and she is flawless in them. Whether or not Dreyer initially courted Lillian Gish for the role, fortune handed him the perfect match in Falconetti. An accomplished stage actress known primarily for light roles, she did not return to the screen after The Passion of Joan of Arc. Indeed, it was her only feature. Her work here is widely considered among the best performances of the silent era.

Although Dreyer developed the movie with a mainstream audience in mind, The Passion of Joan of Arc quickly became known as an "avant garde" motion picture and, as such, it was poorly attended. It was banned in some countries and generated little interest in others. In the United States, its opening went largely unnoticed. Poor attendance and a mixed critical reception were not the only issues that plagued the movie. Before more than a handful of prints had been made, the negative was destroyed in a fire. Dreyer painstakingly created a second negative using alternate takes. Prints were struck from this before it too fell victim to flames. For roughly 50 years (from about 1930 until 1981), the only available editions of The Passion of Joan of Arc were bastardized ones, some with as much as 40% of the material excised by censors. In 1981, an intact version of the original cut was discovered in a mental institution in Oslo; this has been used for all DVD copies. The film's journey is worthy of its subject.

There is no definitive soundtrack for The Passion of Joan of Arc. When it was first screened in 1928 and 1929, there was live music (as for many pre-talkies), but there is no indication that Dreyer had a preferred score. The Criterion version of the DVD provides two versions: one completely silent and one featuring Richard Einhorn's Voices of Light oratorio as the accompaniment. Watching each offers a different perspective. The purely silent treatment allows one to study the craft evident in Dreyer's composition, but it is a relatively sterile experience. The Voices of Light edition, however, has more emotional resonance and is arguably the preferred way to watch the movie (although some purists argue that since Dreyer was not involved in the composition of the score, it is somehow "invalid").

The Passion of Joan of Arc, like many of the great artistic silent films, achieved fame and recognition only after its initial failed theatrical run. Dreyer went to his grave (in 1968) believing his preferred cut of the film to be forever lost, but he at least lived long enough to understand that the scholarly film community recognized this as one of the most respected silent films. In fact, the 1952 Sight & Sound Top 10 films of all-time placed The Passion of Joan of Arc at #7 (it was subsequently #7 in 1972 and #10 in 1992). It remains the most innovative and compelling telling of its subject's tale, even though it omits significant portions of her life. It is among the most powerful early arguments in favor of a minimalist approach to filmmaking and champions the effectiveness of the close-up when used properly. It's hard to imagine anyone today arguing its place in the pantheon of Silent Olympians.

Passion of Joan of Arc, The (France, 1928)

Cast: Maria Falconetti, Eugene Silvain, Andre Berley, Maurice Schutz, Antonin Artaud

Screenplay: Joseph Delteil, Carl Theodor Dreyer

Cinematography: Rudolph Mate

Music: Richard Einhorn (Voices of Light)

U.S. Distributor: M.J. Gourland

- (There are no more better movies of Maria Falconetti)

- (There are no more worst movies of Maria Falconetti)

- (There are no more better movies of Eugene Silvain)

- (There are no more worst movies of Eugene Silvain)

- (There are no more better movies of Andre Berley)

- (There are no more worst movies of Andre Berley)

Comments