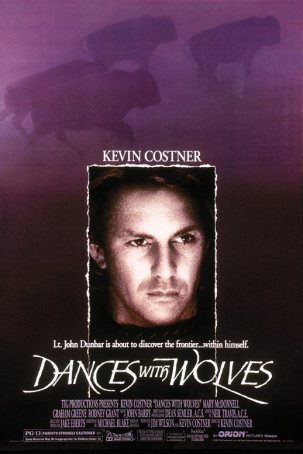

Dances with Wolves (United States, 1990)

There was a time when the western was one of Hollywood's most popular genres. Whether it was Gary Cooper standing tall in High Noon, Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas taking out the Clantons in Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, John Wayne fighting the Apaches in Rio Grande, or Clint Eastwood looking more bad than good or ugly in Sergio Leone's trilogy, the Old West was a sure way to break into the black at the box office. But that was during the '50s and '60s. Since then, another cinematic generation has taken over and the western has gone the way of the musical. In 1990, while it wasn't yet as extinct as the Sabertooth Tiger, it was definitely on the endangered species list - until Kevin Costner came along and singlehandedly breathed new life into the genre. Suddenly, in the span of three years, two westerns had captured the Best Picture Oscar (Dances with Wolves and Unforgiven). And, while this newfound popularity didn't come close to challenging what had once been, film makers could take solace that they would not be summarily denied funding the moment they mentioned the words "Old West."

When Kevin Costner made Dances with Wolves, he was at the height of his popularity. The debacles of Waterworld and The Postman were still years in the future. As an actor, he was riding the crest of a motion picture wave that included Silverado, No Way Out, The Untouchables, Bull Durham, and Field of Dreams. Dances with Wolves, which gave Costner the triple hat of performer, producer, and director, was one of the most ambitious and impressive debuts of any novice film maker in the past three decades. In the '90s, it is only one of two films lasting longer than three hours to have grossed more than $100 million domestically (the other being Titanic), showing that the public loved it as much as the critics.

Dances with Wolves has been called a "revisionist western" - a movie that reversed the traditional roles of Cowboys and Indians. In fact, it's nothing of the sort. While it is true that the Sioux tribe is portrayed with the kind of balance and sensitivity rarely accorded to Native Americans in any movie, the Pawnee do not fare as well (as Sioux enemies, they are presented in much the same fashion that Indians were back in the '50s and '60s). And the American soldiers are depicted as genuine, imperfect human beings, not as thoughtless, vicious brutes. We mourn the death of Lieutenant Elgin as much as that of Stone Calf. So, although Dances with Wolves makes a conscious attempt to set the historical record straight, the role reversal is not complete. This is not meant to minimize Costner's achievement in presenting an epic motion picture from the Native American perspective, but to note that Dances with Wolves did not subvert the entire genre; it just twisted a few of the conventions. Areas that were once presented in graphic black and white have been blurred by the inclusion of many shades of gray.

Dances with Wolves opens with a brief Civil War prologue in which the protagonist, Lt. John Dunbar (Costner), establishes himself as a hero by providing a diversion so that a group of Union soldiers can overcome an entrenched Rebel position. Dunbar's reason for his actions - he preferred losing his life to living without a leg (the doctors were planning an amputation) - are unimportant. All that matters are the results, and, because of his bravery, he is offered a station anywhere he wants. He chooses the frontier, so he can see it before it is gone. Soon, he has been dispatched to the small South Dakota post of Fort Sedgewick. But, when he arrives there in the company of the wagon-driver Timmons (Robert Pastorelli), he finds the place deserted. Nevertheless, he resolves to obey his orders, and, after dismissing Timmons, he sets about putting things to right and solving the mystery of where everyone went.

For over a month, Dunbar is alone at Fort Sedgewick. His only companions are a friendly wolf that he names Two Socks and his faithful mount, Cisco. Gradually, over time, he becomes comfortable with his peaceful surroundings - some of the most beautiful country he has ever seen. The sequences with Dunbar alone at Sedgewick are some of the best in the movie. There is a kind of quiet cinematic poetry in these scenes as we grow not only to learn about the character of Dunbar, but about the land itself - not as it is today, but as it was 135 years ago. The first hour of Dances with Wolves is setup, but the gorgeous visuals, lush score (by John Barry), and reflective tone makes it a pleasant introduction.

The story moves into high gear with the arrival of the Sioux, led by the thoughtful Kicking Bird (Graham Greene) and the tempestuous Wind in His Hair (Rodney A. Grant). At first, there is mutual distrust, but, as Dunbar and the Sioux interact and begin to communicate (each learning a few words of the other's language), they form a truce, then a bond. With every passing day, Dunbar finds himself more and more infatuated with the Sioux way of life. And his interaction with them becomes even easier when Stands With A Fist (Mary McDonnell), a white woman who has lived with the Sioux since childhood, is able to act as an interpreter. Eventually, Dunbar leaves Fort Sedgewick and moves into the Sioux camp. He falls in love with Stands with a Fist, becomes a respected member of the tribe with his own Sioux name ("Dances With Wolves"), and is able to forget the life he left behind - until the day when Fort Sedgewick is garrisoned and the soldiers find him: an out-of-uniform officer "gone Injun."

Dances with Wolves works on many levels. It's a rousing adventure, a touching romance, and a stirring drama. While Dunbar's story is fictional, the background surrounding it is real, from the Sioux beliefs to the "take without asking" policy of many frontiersmen. Costner was determined to make the film as authentic as possible. He did most of his own stunts. Instead of using a half-breed for Two Socks, he used a full wolf. The Sioux speak their own language, Lakota (with subtitles), instead of English. And Costner cast only Native Americans as Indians.

The characters populating Dances with Wolves are strongly written and effectively portrayed. While no one is going to place Costner alongside Laurence Olivier in the acting department, he brings a likability to Dunbar that many better performers might not have been able to match. The film works in large part because we identify so thoroughly with Dunbar. In fact, we know nothing of his past - he comes to us as a clean slate, born through his act of suicidal courage. We never learn anything about his family or childhood, but we see the frontier and the Sioux culture through his eyes, and it quickly becomes apparent that for him, the past is irrelevant. The reality of his life begins when we first meet him.

To say that the Sioux defy traditional stereotypes is to understate the matter. As portrayed by Graham Greene, Rodney A. Grant, Floyd Red Crow Westerman, Tantoo Cardinal, and others, these are a group of compelling, diverse characters who show no hint of caricature. Mary McDonnell plays an effective love interest for Dunbar. Like him, Stands With A Fist is caught between two cultures. Costner should be applauded for this casting choice. McDonnell has the maturity to make certain scenes work when a younger actress might have struck a false note (McDonnell is three years older than Costner). The director was determined that Stands With A Fist should be portrayed by a "woman," not a "girl."

Although Dances with Wolves contains several well-executed battle scenes, there's little doubt that the most breathtaking sequence is the buffalo hunt, where the Sioux riders race alongside thousands of rampaging buffalo and bring several of them down. It's a high adrenaline sequence that marks the moment when Dunbar finally rejects his old culture to embrace his new one. From a technical and logistical perspective, this is probably the year's singlemost memorable scene, and the adroitness with which Costner directed it explains (at least in part) why he won the Best Director Oscar.

For several years after Dances with Wolves, expectations were high about Costner's next project. Sadly, when it finally materialized in late 1997, The Postman was a colossal disappointment. Will Costner ever direct again? At this point, that question cannot be answered, but, even if he never makes another film, he can be proud of the singular achievement on his resume. For three hours, Dances with Wolves transports us to another world, and that's the mark of a great motion picture.

Dances with Wolves (United States, 1990)

Cast: Maury Chaykin, Jimmy Herman, Charles Rocket, Robert Pastorelli, Tantoo Cardinal, Floyd Red Crow Westerman, Rodney A. Grant, Graham Greene, Mary McDonnell, Kevin Costner, Nathan Lee Chasing His Horse

Screenplay: Michael Blake, based on his novel

Cinematography: Dean Semler

Music: John Barry

U.S. Distributor: Orion Pictures

U.S. Release Date: -

MPAA Rating: "PG-13" (Violence, Sexual Situations, Nudity)

Genre: WESTERN

Subtitles: Some English subtitled Lakota

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 2.35:1

- Cutthroat Island (1995)

- Adjuster, The (1969)

- (There are no more worst movies of Maury Chaykin)

- (There are no more better movies of Jimmy Herman)

- (There are no more worst movies of Jimmy Herman)

- (There are no more better movies of Charles Rocket)

- Dumb and Dumber (1994)

- (There are no more worst movies of Charles Rocket)

Comments