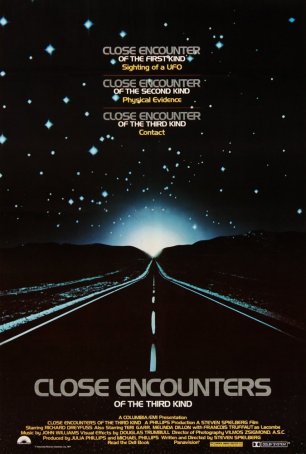

Close Encounters of the Third Kind (United States, 1977)

In late 1977, everyone seemed to believe this. Although UFOs have been a popular subject for speculation, rumination, and investigation for more than 50 years, at no time was the phenomenon more popular than during the 1970s. Along with the Loch Ness Monster, Bigfoot, and the Abominable Snowman, UFOs were no longer the province of "fringe" elements, but had moved into the mainstream. There were plenty of skeptics, but many people, including those who had never purported to see anything out-of-the-ordinary, wanted to believe. Maybe it had something to do with the world order being so bleak (racial tension, Vietnam, the Cold War), but more and more men and women looked to the stars to find hope.

Close Encounters of the Third Kind is a great movie, but it also benefited from peerless timing. Released on the heels of Star Wars, it was able to absorb the pro-Science Fiction atmosphere that had arisen as a result of George Lucas' unexpected blockbuster. Suddenly, everyone was into stories about space and aliens. And, while Close Encounters is a much different film than Star Wars, it played to the same audience. First, we were given the opportunity to see what it was like a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away. Then, we were allowed to see what it was like here on Earth when visitors come calling.

Close Encounters represented an opportunity for director Steven Spielberg to tell a story he had been wanting to tell for years - what might happen if benevolent aliens made contact with human beings. Spielberg had been working on the story since before he began filming Jaws and, even after Close Encounters was "in the can" in late 1977, the director wasn't done with it. Consequently, the version that was rushed into theaters in November 1977 did not represent Spielberg's final vision. Armed with $2 million, the director went back behind the camera to shoot additional scenes, then returned to the editing room. Close Encounters of the Third Kind: The Special Edition was released in 1980. It represented a re-working of the 1977 edition (which Spielberg referred to as a "work-in-progress"), with about 15 minutes of original footage deleted, and another 12 minutes of new scenes (including six minutes inside the ship at the end) added. Since then, there have been at least four other versions, all incorporating various combinations of the deleted scenes, and ranging in length from 132 minutes to nearly 2 1/2 hours. From a thematic and content perspective, they are all similar. The differences are minor, with no particular version standing out as obviously better than any of the others. For the record, this review is based on the latest "Collector's Edition" of the film, which is available on DVD. That motion picture cut is heavily based on the 1977 version, with a few of the 1980 scenes included. The selling gimmick of the Special Edition - the six minute epilogue with Richard Dreyfuss in the alien craft - is included as a deleted scene, but is not a part of the actual movie. (Spielberg is on record as calling that sequence a mistake - he now argues that the inside of the ship should never have been shown.)

Close Encounters represented an opportunity for director Steven Spielberg to tell a story he had been wanting to tell for years - what might happen if benevolent aliens made contact with human beings. Spielberg had been working on the story since before he began filming Jaws and, even after Close Encounters was "in the can" in late 1977, the director wasn't done with it. Consequently, the version that was rushed into theaters in November 1977 did not represent Spielberg's final vision. Armed with $2 million, the director went back behind the camera to shoot additional scenes, then returned to the editing room. Close Encounters of the Third Kind: The Special Edition was released in 1980. It represented a re-working of the 1977 edition (which Spielberg referred to as a "work-in-progress"), with about 15 minutes of original footage deleted, and another 12 minutes of new scenes (including six minutes inside the ship at the end) added. Since then, there have been at least four other versions, all incorporating various combinations of the deleted scenes, and ranging in length from 132 minutes to nearly 2 1/2 hours. From a thematic and content perspective, they are all similar. The differences are minor, with no particular version standing out as obviously better than any of the others. For the record, this review is based on the latest "Collector's Edition" of the film, which is available on DVD. That motion picture cut is heavily based on the 1977 version, with a few of the 1980 scenes included. The selling gimmick of the Special Edition - the six minute epilogue with Richard Dreyfuss in the alien craft - is included as a deleted scene, but is not a part of the actual movie. (Spielberg is on record as calling that sequence a mistake - he now argues that the inside of the ship should never have been shown.)

Alien visitations to Earth are a staple of science fiction. Some of the best (The Day the Earth Stood Still) and worst (Plan Nine from Outer Space) genre entries have used that subject matter as a launching pad. One of the things that differentiates Close Encounters from its seemingly countless predecessors is that the aliens are friendly, curious, and even playful. Mr. Spock aside, this is not a common characterization of space-faring races. More often than not, aliens in motion pictures are shown attacking Earth, not observing and trying to make peaceful contact. Films like Close Encounters, E.T., and Contact are exceptions to the rule.

What would first contact really be like? That's the scenario Spielberg imagined with the aid of Dr. J. Allen Hynek, one of the world's foremost "serious" UFO experts. The military is involved, but they aren't running the show; instead, scientists are in charge. The encounter is a wonderful, magical meeting of cultures - humans putting their efforts not into weapons and fighting, but into the simplest and most important of life's basics: communication. Through colors, music, and hand gestures, we forge an understanding with an alien species. Given a choice between this and Independence Day, not only is Close Encounters more plausible, but infinitely preferable.

The plot is simple and straightforward, unburdened by pointless twists and turns. Close Encounters focuses on three characters and the different paths that bring them together at Devil's Tower, Wyoming, for the climax. First, there's Roy Neary (Dreyfuss), an everyday kind-of-guy with three kids and a materialistic wife (Teri Garr) who's hyper-concerned about what the neighbors will think. For his part, Roy's still a kid at heart, loving goofy golf and going to the movies to see Pinocchio. Roy works for the power company, and, one night, during an area-wide blackout, he has a close encounter with an alien spaceship that leaves half of his face sunburned and his psyche shaken. Suddenly, Roy's family becomes secondary to his obsession about aliens. He has unexplained visions of a mountain, and is compelled to make models of it out of whatever materials are available.

The plot is simple and straightforward, unburdened by pointless twists and turns. Close Encounters focuses on three characters and the different paths that bring them together at Devil's Tower, Wyoming, for the climax. First, there's Roy Neary (Dreyfuss), an everyday kind-of-guy with three kids and a materialistic wife (Teri Garr) who's hyper-concerned about what the neighbors will think. For his part, Roy's still a kid at heart, loving goofy golf and going to the movies to see Pinocchio. Roy works for the power company, and, one night, during an area-wide blackout, he has a close encounter with an alien spaceship that leaves half of his face sunburned and his psyche shaken. Suddenly, Roy's family becomes secondary to his obsession about aliens. He has unexplained visions of a mountain, and is compelled to make models of it out of whatever materials are available.

The second character is Jillian Guiler (Melinda Dillon), a mother who has lost her young son, Barry (Cary Guffey), to the aliens. One night, they arrive at Jillian's house and take Barry away. Now, like Roy, she is obsessed by the image of the mountain, except, instead of making sculptures, she draws, aware that there is some connection between her artwork and the opportunity to be re-united with her son. She meets Roy at the time of the first alien appearance and ends up joining with him for a road trip after his wife and family have left him.

Finally, there's U.N. scientist Claude Lacombe (François Truffaut), the man in charge of a mostly-American team investigating unexplained phenomena around the globe and preparing a huge staging area for Earth's first contact with visitors from the stars. Lacombe is focused and humorless, but not unkind. When he recognizes that Jillian and Roy have been "invited" by the aliens to be at Devil's Tower, he does what little he can (without being overt) to assist them. In the end, however, Lacombe is more concerned with the aliens than he is with the humans.

Part of the genius of Close Encounters is that we don't know until the end that the aliens are not hostile. Some of their early appearances in the film (when they shake Roy's power truck and visit Jillian's home to abduct Barry) are unsettling. Think of the furnace-like red light that envelopes Jillian's house as the alien craft approaches. Red is traditionally not a comforting color, and, in this case, it's downright frightening. (This is perhaps the only scene in the film that may scare younger children.) Unlike E.T., Close Encounters does not have a light, playful tone. There is an almost ominous undercurrent to the proceedings. Only in the end, when Spielberg pulls back the curtain on an awe-inspiring, majestic climax, do we finally understand that not being alone does not mean being in danger. We have to unlearn all that nearly every other motion picture has taught us about alien visitations.

Close Encounters is one of those rare films that works equally as well for children and for adults. Kids see this film as a promise of what might be out there and an unthreatening look at the possibilities that the universe holds. How many UFO believers today began their fascination with alien life after seeing this movie as a child? Adults, even skeptics, see Close Encounters as an accomplished fairy tale. Whether UFOs are real or not, this movie beautifully postulates the best of all alternatives - that the government cares about first contact and about the welfare of its citizens, that the aliens are benevolent, and that we can take comfort from the fact that "we are not alone". Remarkably, a film like Close Encounters speaks to the adult in the child and the child in the adult.

Close Encounters does not feature any "big name" stars, but the effectiveness of the casting is crucial to its success. Richard Dreyfuss, who worked with Spielberg on Jaws and, between takes on that movie learned of the filmmaker's plans to direct Close Encounters, won the role only after a hard-fought campaign. Spielberg's first choice was Steve McQueen, who loved the script, but turned down the part of Roy because he had never mastered the art of crying on screen. Dreyfuss was not Spielberg's second or even third option, but his tireless persistence got him the part in the wake of several bigger name refusals. It's a case of serendipity, because Dreyfuss fits perfectly into the "everyman" persona necessary for Roy to connect with the audience. We see ourselves on screen.

Close Encounters does not feature any "big name" stars, but the effectiveness of the casting is crucial to its success. Richard Dreyfuss, who worked with Spielberg on Jaws and, between takes on that movie learned of the filmmaker's plans to direct Close Encounters, won the role only after a hard-fought campaign. Spielberg's first choice was Steve McQueen, who loved the script, but turned down the part of Roy because he had never mastered the art of crying on screen. Dreyfuss was not Spielberg's second or even third option, but his tireless persistence got him the part in the wake of several bigger name refusals. It's a case of serendipity, because Dreyfuss fits perfectly into the "everyman" persona necessary for Roy to connect with the audience. We see ourselves on screen.

Melinda Dillon, who earned a Best Supporting Actress nomination for her work, was not cast until the weekend before she was due to begin filming. Like Dreyfuss, she develops her character into someone it's easy for the average man or woman to sympathize with. There's nothing special or extraordinary about Jillian - she's a single mother who will brave any odds to be reunited with her son. In another movie, she might end up being Roy's "love interest", but Spielberg keeps the attraction between the two strictly platonic.

The casting of François Truffaut was Spielberg's coup. Truffaut was the dream choice for the part, and Spielberg didn't expect the great French filmmaker to say yes. Truffaut is, of course, far better known for his work behind the camera (which includes such classics as The 400 Blows and Jules et Jim) than in front of it. As an actor, he has a handful of roles to his credit, the only significant international one of which is Lacombe. (It's interesting to consider how many American children during the late '70s got their first exposure to Truffaut through this film.) Truffaut made it clear from the beginning that he was in Close Encounters to work as an actor and not to function as a second director looking over Spielberg's shoulder. He acquits himself admirably, bringing a dignity and seriousness to the part that is appropriate for his stature.

At the beginning of 1977, composer John Williams was very well known in Hollywood (primarily for his work in television and several Oscar-nominated scores dating back to 1967). However, this was the year that would catapult him to the A-list, joining such luminaries as Ennio Morricone, Jerry Goldsmith, and John Barry. At the 1978 Academy Award celebration, Williams faced off against himself. While he won for Star Wars, with its bolder, brasher music, one could make an argument that his work for Close Encounters (for which he was also nominated) was more accomplished. Indeed, the signature five notes linger in the memory today, and, at the time, everyone with a musical instrument knew how to play them. (Ironically, there was nothing special about that combination. Williams and Spielberg eventually picked it out of hundreds of possibilities because they needed something, not because it stood out.) Aside from the principle notes, the Close Encounters score is low-key, doing what good movie music should do: setting the mood, but not overpowering the screen action.

At the beginning of 1977, composer John Williams was very well known in Hollywood (primarily for his work in television and several Oscar-nominated scores dating back to 1967). However, this was the year that would catapult him to the A-list, joining such luminaries as Ennio Morricone, Jerry Goldsmith, and John Barry. At the 1978 Academy Award celebration, Williams faced off against himself. While he won for Star Wars, with its bolder, brasher music, one could make an argument that his work for Close Encounters (for which he was also nominated) was more accomplished. Indeed, the signature five notes linger in the memory today, and, at the time, everyone with a musical instrument knew how to play them. (Ironically, there was nothing special about that combination. Williams and Spielberg eventually picked it out of hundreds of possibilities because they needed something, not because it stood out.) Aside from the principle notes, the Close Encounters score is low-key, doing what good movie music should do: setting the mood, but not overpowering the screen action.

The film's special effects are remarkable for their era, dwarfing everything that had come before (including Star Wars and 2001). The mother ship in particular is an amazing creation, and, as it hovers over Devil's Tower late in the film (and in one of the posters for the movie), it's impossible to tell that this is the result of post-production wizardry rather than something genuinely in the sky. Much of Close Encounters passes without major effects; yet, when Spielberg calls upon the genius of Douglas Trumbull (who previously worked on 2001 and Silent Running, and would go on to supervise the visual effects for Star Trek: The Motion Picture and Blade Runner) to provide a jaw-dropping climax, the master delivers exactly what's needed.

Close Encounters of the Third Kind is peerless in the field of first-contact films - its eight Oscar nominations and one win (Best Cinematography) are a testimony to that. Its universal appeal gave movie-goers something to be excited about during the winter of 1977-78 as the first in a wave of post-Star Wars science fiction films broke (although, of course, Close Encounters went into production long before Star Wars reached screens). Today, at the time of its 40th anniversary, the movie stands up remarkably well. The story is fresh and compelling, the special effects are as remarkable as anything that CGI can do, and the music represents some of John Williams' best work. Close Encounters is the complete package, and it shines as brightly in its latest iteration as it did in its first.

Close Encounters of the Third Kind (United States, 1977)

Cast: Richard Dreyfuss, François Truffaut, Teri Garr, Melinda Dillon, Bob Balaban, Cary Guffey

Screenplay: Steven Spielberg

Cinematography: Vilmos Zsigmond

Music: John Williams

U.S. Distributor: Columbia Pictures

U.S. Release Date: 1977-12-14

MPAA Rating: "PG" (Mature Themes)

Genre: Science Fiction

Subtitles: none

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 2.35:1

- (There are no more better movies of François Truffaut)

- (There are no more worst movies of François Truffaut)

- Tootsie (1982)

- (There are no more better movies of Teri Garr)

- (There are no more worst movies of Teri Garr)

Comments