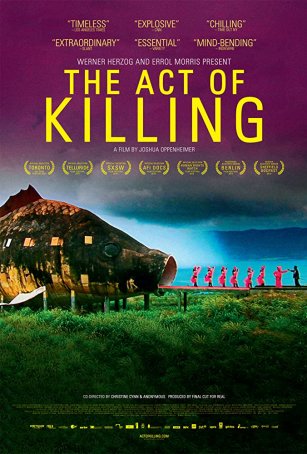

Act of Killing, The (U.K./Denmark/Norway, 2012)

March 29, 2020

Rarely have I felt as conflicted as I did while watching Joshua Oppenheimer’s 2012 documentary, The Act of Killing. Over the course of its nearly three-hour running time, the movie does many things, some of which are wrenching, some of which pose unanswerable existential questions, and some of which make one wonder whether the film should exist in the first place. Is this movie a look into the mind of a mass murderer? Is it an attempt to understand what Hannah Arendt called “the banality of evil?” Or is it an opportunity by a top death squad executioner to rehabilitate his image and garner some free propaganda? Perhaps, by intent or accident, it’s all three.

Certainly, director Joshua Oppenheimer has achieved something with The Act of Killing that no previous filmmaker has attempted. Bolstered by the plaudits of Errol Morris and Werner Herzog (both of whom received Executive Producer credits), the movie achieved enormous critical acclaim during its limited theatrical release and even better press when the longer, more complete director’s cut came out two years later. (For purposes of this review, I watched the director’s cut.) A minority of reviewers, however, broke violently in the opposite direction. Peter Rainer, writing for The Christian Science Monitor, had the following to say: “I was… repelled by this film’s conceit. Oppenheimer allows murderous thugs free rein to preen their atrocities, and then fobs it all off as some kind of exalted art thing. This is more than an aesthetic crime; it’s a moral crime.” While I don’t entirely agree with Rainer – I think the film has more value than he’s giving it credit for – I understand his repugnance. For some, The Act of Killing will be unwatchable. For those who can endure it, the experience will give no pleasure.

The two subjects, Anwar Congo and Herman Koto, were death

squad leaders in the 1965 Indonesian massacre of a million so-called

“communists” and ethnic Chinese. They were celebrated for their murderous deeds

and, to this day, they are revered as heroes and patriots. They do not hide

their pasts. If anything, they revel in their deeds. Congo, whom the film

focuses on the most, is said to have killed 1000 people. To look at him now, as

Oppenheimer’s camera does, he fits the image of a kindly grandfather. He claims

to resemble the American actor Sidney Poitier. He has a genial smile, even if

the straightness of his teeth is the result of dentures. It creates a sense of

cognitive dissonance to connect this seemingly mild-mannered man with the

monster of his past. It’s even stranger to hear him talking about his actions

in a matter-of-fact fashion.

The two subjects, Anwar Congo and Herman Koto, were death

squad leaders in the 1965 Indonesian massacre of a million so-called

“communists” and ethnic Chinese. They were celebrated for their murderous deeds

and, to this day, they are revered as heroes and patriots. They do not hide

their pasts. If anything, they revel in their deeds. Congo, whom the film

focuses on the most, is said to have killed 1000 people. To look at him now, as

Oppenheimer’s camera does, he fits the image of a kindly grandfather. He claims

to resemble the American actor Sidney Poitier. He has a genial smile, even if

the straightness of his teeth is the result of dentures. It creates a sense of

cognitive dissonance to connect this seemingly mild-mannered man with the

monster of his past. It’s even stranger to hear him talking about his actions

in a matter-of-fact fashion.

Part of the problem is that Oppenheimer is so focused on Congo that he does little more than sketch in events of the 1960s. There’s no contemporaneous footage or interviews with Congo’s victims or the surviving relatives of those who were killed. A case could be made that, during the lengthy period he spent with Congo, Oppenheimer developed sympathy for the man. Which leads to a central question: Are there any crimes so heinous that redemption is impossible? The Act of Killing doesn’t pose this question directly and it certainly can’t answer it, but it infuses every frame, the elephant in the room.

The “conceit” that so angered Rainer is when Oppenheimer

provides Congo and Koto opportunities to re-enact their “greatest hits” on

film. Congo, who reveres American gangster movies, uses techniques as diverse

as musical numbers and nods to Scarface to dramatize incidents from his

life and career. We are privy to the behind-the-scenes crafting of these

moments and Oppenheimer presents the scenes in their entirety. The project,

begun with enthusiasm by Congo and publicized by him on a TV chat show, is not

without an impact. So many years after committing genocide, Congo displays

indications of guilt and remorse. At one point, late in the film, he breaks

down. The shattering of his blasé shell might be heartbreaking if one was to

forget about the thousands upon thousands of lives he destroyed.

The “conceit” that so angered Rainer is when Oppenheimer

provides Congo and Koto opportunities to re-enact their “greatest hits” on

film. Congo, who reveres American gangster movies, uses techniques as diverse

as musical numbers and nods to Scarface to dramatize incidents from his

life and career. We are privy to the behind-the-scenes crafting of these

moments and Oppenheimer presents the scenes in their entirety. The project,

begun with enthusiasm by Congo and publicized by him on a TV chat show, is not

without an impact. So many years after committing genocide, Congo displays

indications of guilt and remorse. At one point, late in the film, he breaks

down. The shattering of his blasé shell might be heartbreaking if one was to

forget about the thousands upon thousands of lives he destroyed.

Oppenheimer knows he has powerful, combustible material but he has difficulty shaping it into something resembling a coherent narrative. There are too many threads and the film’s moral compass is at best dubious. Some sequences last too long and many of the amateurish recreations become tedious to watch. The lack of a strong historical background (including the missing voices of the victims) puts the onus on the viewer to remember who and what Congo was.

To watch The Act of Killing is to be provided with a glimpse of how some truly evil people perceive themselves and their reality. It’s an ugly and unsettling thing. The movie has value and will leave an impression on anyone who watches it. But the questions remain. I can’t call The Act of Killing a great film but neither can I dismiss it. So I will give it an entirely inadequate three-star rating that serves as an admission that conventional rating tools fail with a movie like this.

Act of Killing, The (U.K./Denmark/Norway, 2012)

Cast: Anwar Congo, Herman Koto

Home Release Date: 2020-03-29

Screenplay: Joshua Oppenheimer

Cinematography: Carlos Arango De Montis, Lars Skree, Anonymous

Music:

U.S. Distributor: Drafthouse Films

U.S. Release Date: 2013-07-19

MPAA Rating: "NR" (Violence)

Genre: Documentary

Subtitles: In Indonesian with subtitles

Theatrical Aspect Ratio: 1.85:1

- (There are no more better movies of Anwar Congo)

- (There are no more worst movies of Anwar Congo)

- (There are no more better movies of Herman Koto)

- (There are no more worst movies of Herman Koto)

Comments